Train track maps, which also come in “relative” and other flavors, are particularly nice homotopy equivalences of graphs used as tools to reason about outer automorphisms of free groups. I wrote a paper extending train track maps (as well as relative train track maps and “CTs”) to graphs of groups (with trivial edge groups for CTs). In this post I want to talk a little about how to think about train track maps and (“tame” in some sense) homotopy equivalences of graphs of groups more generally. At the end of the post I talk through using the train track algorithm to compute an example coming from a pseudo-Anosov 5-braid.

Background on graphs of groups

First, a little background for anyone reading who isn’t an expert in graphs of groups. The standard reference is Chapter 1 of Serre’s book Trees, which is terse but very good. Group actions on trees (i.e. simply connected, 1-dimensional simplicial complexes) crop up all over the place in the theory of infinite groups. A graph of groups is a kind of “orbifold quotient” of a group action on a tree. Technically one needs to assume that the action satisfies the condition of “no inversions in edges” which means what it probably sounds like and can always be accomplished by passing to the barycentric subdivision of the tree. Under this hypothesis, the quotient space of the action is naturally a graph (i.e. a 1-dimensional CW complex, which will be connected). Attached to the vertices and edges of the graph are groups recording stabilizer information. The “no inversions in edges” hypothesis ensures that if an edge is stabilized by a group element, then so are the incident vertices, so there are injective homomorphisms from edge groups into incident vertex groups.

If you happen to like thinking categorically, a graph of groups can be succinctly described this way. A graph $\Gamma$ describes a small category $\Gamma$ whose objects are the cells of $\Gamma$ and whose nonidentity arrows run from edges to incident vertices. A graph of groups is a functor from the small category $\Gamma$ to the category of groups with arrows monomorphisms.

The fundamental theorem of Bass–Serre theory asserts a perfect correspondence between groups acting on trees on the one hand and graphs of groups on the other. The exciting part of the theorem says that given a graph of groups, there is a group, called the fundamental group of the graph of groups and a tree, called the Bass–Serre tree on which it acts so that the quotient graph of groups is the given graph of groups. By the way, the fundamental group is really a group of homotopy classes of loops in the right sense. In the language of orbifolds, every graph of groups is “good.” What’s more, a simple presentation of the fundamental group of the graph of groups can be written down, and the tree and action explicitly described.

Morphisms and maps of graphs of groups

Let’s call a continuous map of graphs a morphism if it sends vertices to vertices and edges to edges. There is a notion, due to Bass, of a morphism of graphs of groups. It’s a little complicated, so I’d rather talk around it than give a formal definition here. Suppose $G$ and $G'$ are groups acting on trees $T$ and $T'$ , respectively, and suppose that we have a homomorphism $f_\sharp\colon G \to G'$ . A morphism $\tilde f\colon T \to T'$ is equivariant with respect to $f_\sharp$ if for all $g \in G$ and $x \in T$ , we have

$\tilde f(g.x) = f_\sharp(g).\tilde f(x).$If $\mathcal{G}$ and $\mathcal{G}'$ are the quotient graphs of groups, Bass’s definition is designed so that in this situation there is a morphism $f\colon\mathscr{G} \to \mathscr{G}'$ . Conversely, given a morphism of graphs of groups $f\colon \mathscr{G} \to \mathscr{G}'$ , there is a map $f_\sharp\colon G \to G'$ and an equivariant map $\tilde f\colon T\to T'$ . The correspondence is not quite perfect—in some situations there are multiple morphisms of graphs of groups yielding the same pair $f_\sharp$ and $\tilde f$ , but the difference is understood.

If one happens to be categorically minded, it’s possible to give a succinct definition of a morphism of graphs of groups. Suppose $\mathcal{G}$ and $\mathcal{G}'$ are graphs of groups with underlying graphs $\Gamma$ and $\Gamma'$ , respectively. A morphism of graphs $f\colon \Gamma \to \Gamma'$ yields a functor of the associated small categories. (Indeed, one could eke out slightly more generality by defining morphisms of graphs to be those maps yielding a functor of small categories.) A morphism of graphs of groups is a morphism of underlying graphs $f\colon \Gamma \to \Gamma'$ and a pseudonatural transformation of functors $f\colon \mathscr{G} \Rightarrow \mathscr{G}'f$ .

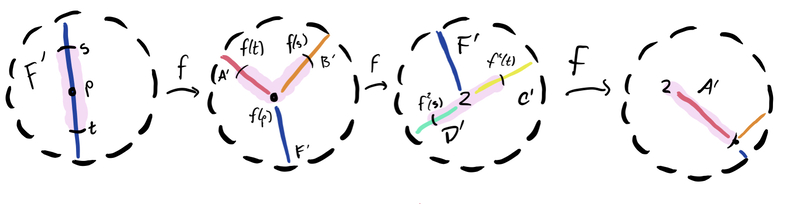

Now suppose we have an automorphism $f_\sharp\colon G \to G$ and a map $\tilde f \colon T \to T$ which is equivariant with respect to $f_\sharp$ but may not be a morphism. After performing a homotopy, we may assume that $\tilde f$ is a linear embedding on each edge, expanding it over an edge path. Now $\tilde f$ will become a morphism after (equivariantly) subdividing each edge into finitely many edges, so on the quotient graph of groups we are interested in maps which may be represented as a subdivision followed by a morphism. Such a map $f\colon \mathcal{G}\to\mathcal{G}$ sends vertices to vertices and edges to paths in the graph of groups. If additionally the image of each edge is a tight path, i.e. it cannot be shortened by a homotopy, we’ll call such a map a topological representative. For (many) examples of this kind of map, hang on for one more section.

Train track maps

Train track maps were introduced by Bestvina and Handel in their 1992 paper “Train tracks and automorphisms of free groups” to study outer automorphisms of free groups. They remain one of the main tools for their study. A topological representative is a train track map if for each edge $e$ , the path $f^k(e))$ is immersed for all $k \ge 1$ , i.e. it cannot be shortened by a homotopy. If one accepts immersions and homotopy in a graph of groups sense, the same definition works for both topological representatives on graphs and on graphs of groups.

Bestvina and Handel describe an algorithm that takes as input an arbitrary topological representative and progressively either improves it to a train track map or finds an invariant subgraph. (It is a priori possible to be both a train track map and have an invariant subgraph, but these cases are of less interest.)

The argument is a beautiful application of the Perron–Frobenius theory of nonnegative integer matrices. A nonnegative integer matrix $M$ is irreducible if for each $i$ and $j$ there exists $k$ such that the $ij$ th entry of $M^k$ is positive. To a topological representative $f\colon \mathcal{G} \to \mathcal{G}$ we can associate a transition matrix with rows and columns for each edge of the underlying graph $\Gamma$ and $ij$ th entry the number of times the image of the $j$ th edge crosses the $i$ th edge in either direction. It turns out that the transition matrix of $f$ is irreducible exactly when $f$ has no invariant subgraph.

Each irreducible matrix has a real Perron–Frobenius eigenvalue $\lambda$ satisfying $\lambda \ge 1$ . If $f$ is not a train track map, Bestvina and Handel argue, then the Perron–Frobenius eigenvalue may be decreased by their algorithm. But by arguing that the number of edges of the graphs they consider remains bounded, the Perron–Frobenius eigenvalue can only be decreased finitely many times before reaching a minimum, at which point a train track map is reached.

A pseudo-Anosov braid example

To illustrate the algorithm and hopefully offer some illumination on how to think about maps of graphs of groups, I’d like to compute a train track map for the pseudo-Anosov 5-braid with the least dilatation, $\sigma_1\sigma_2\sigma_3\sigma_4\sigma_1\sigma_2$ , seen as an (outer) automorphism of $W_5$ , the free product of 5 copies of the cyclic group of order 2.

Write

$W_5 = \langle a_1,a_2,\dotsc,a_5 \mid a_1^2 = a_2^2 = \dotsb = a_5^2 = 1 \rangle.$There is a homomorphism from the braid group $B_n$ to $\operatorname{Aut}(W_n)$ sending the generator $\sigma_i$ to the automorphism

There’s a good reason (involving orbifolds) that the homomorphism sends pseudo-Anosov braids to (outer) automorphisms representable by irreducible train track maps, but let us just remark that we expect our eventual train track map to have Perron–Frobenius eigenvalue equal to the dilatation of $\sigma_1\sigma_2\sigma_3\sigma_4\sigma_1\sigma_2$ , that is, $\lambda \approx 1.722$ , the largest root of $x^4 - x^3 - x^2 - x + 1$ .

Under the homomorphism, the action of our element on the generators of $W_5$ is given by

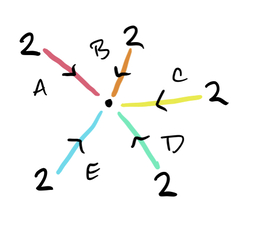

To start, we need a graph of groups with fundamental group $W_5$ . It is a fact that if all edge groups in a graph of groups are trivial, and the underlying graph is a tree, then the fundamental group of the graph of groups is isomorphic to the free product of the vertex groups. Thus a good candidate is the following graph of groups $\mathcal{G}_1$ .

There is one vertex with trivial vertex group, five vertices with vertex group cyclic of order 2, represented in the image by a number 2, and five edges, each one connecting a vertex with nontrivial vertex group to the vertex with trivial vertex group. Let us base the fundamental group at the center vertex with trivial vertex group. Under our identification of this fundamental group with $W_5$ , a generator of $W_5$ is represented by a loop that travels out along an edge, picks up the nontrivial element of the vertex group, and then travels back. Thus for example $a_2$ is represented by the loop $\bar Ba_2B$ .

Let’s introduce some notation: I’ll write a period for the nontrivial element of any vertex group, and write a hat above an edge to mean traveling along the edge, picking up the nontrivial element of the vertex group and then traveling back. Thus the group element $a_1a_2a_3a_2^{-1}a_1^{-1}$ is represented in our graph of groups by the loop $\hat A\hat B\hat C\hat B\hat A$ .

We may represent $\sigma_1\sigma_1\sigma_3\sigma_4\sigma_1\sigma_2$ by the map $f_1\colon \mathcal{G}_1\to\mathcal{G}_1$ defined as

The transition matrix of $f_1$ is

whose Perron–Frobenius eigenvalue $\lambda_1$ is the largest real root of $-x^5 + 4x^4 + 2x^3 + 4x + 1$ and satisfies $\lambda_1 \approx 4.577$ .

How do we decide whether $f_1$ is a train track map? Since $f_1$ sends edges to tight edge paths, the only place where cancellation could occur is where the images of edges are joined together. For example, in $f_1^2(A)$ , there is cancellation between $f_1(B)$ and $f_1(\bar A)$ because the last edge of $f_1(B)$ , namely $A$ , is equal to the reverse of the first edge of $f_1(\bar A)$ . Thus we know $f_1$ is not a train track map.

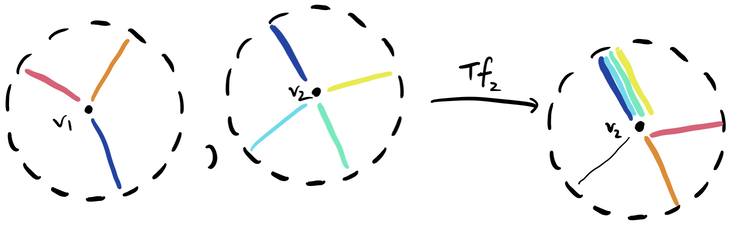

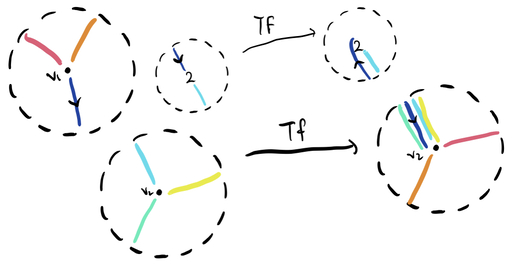

We can formalize this as follows: a turn is a pair of edges sharing a common initial vertex, e.g. $\{\bar A,\bar A\}$ or $\{\bar B,\bar C\}$ . The former turn is degenerate, while the latter is not. If the vertex in question has nontrivial vertex group, rather than just pairs of edges, we should consider pairs of pairs consisting of an edge together with a vertex group element. Thus at the initial vertex of the edge $A$ , the turn $\{.A,A\}$ is nondegenerate. A topological representative $f\colon \mathcal{G} \to \mathcal{G}$ induces a map $Tf$ on the set of turns by sending $\{E,E'\}$ to the turn determined by the initial edges in the image of $f(E)$ and $f(E')$ . A turn is illegal if it is eventually mapped to a degenerate turn. In our example, every turn based at the center vertex is illegal because each such turn is mapped to $\{\bar A,\bar A\}$ . Thus we can say that $f_1$ is not a train track map because, for instance, the image of $f_1(A)$ contains the illegal turn $\{\bar B,\bar A\}$ .

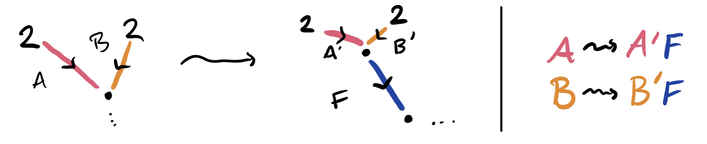

To improve the situation, let’s fold $\bar A$ and $\bar B$ . They each have initial segments mapped to the path $\hat A\hat B$ , so subdivide at the endpoint of these initial segments and then identify them to create a new edge as pictured.

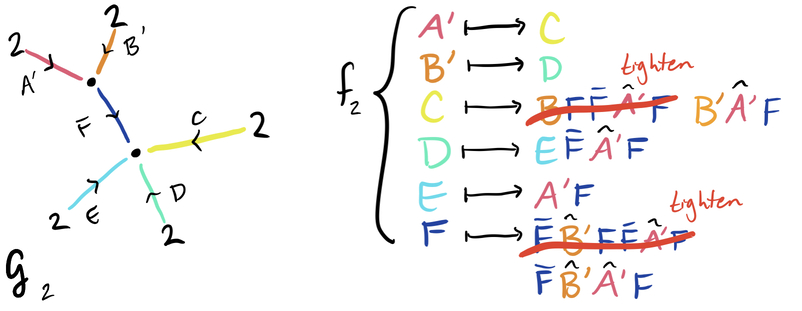

The correspondence $A \leadsto A'F$ and $B \leadsto B'F$ allows us to define a new map on our new graph of groups $f_2\colon \mathcal{G}_2\to \mathcal{G}_2$ . The new map admits some tightening, which yields a corresponding reduction in the Perron–Frobenius eigenvalue $\lambda_2$ , which is now the largest root of the polynomial $x^6 - 2x^5 - 2x^4 - 4x^2 + 3x + 2$ and satisfies $\lambda_2 \approx 2.994$ .

However, the map $f_2$ is still not a train track map, since every turn based at either of the vertices with trivial vertex stabilizer is eventually mapped to $\{\bar F,\bar F\}$ .

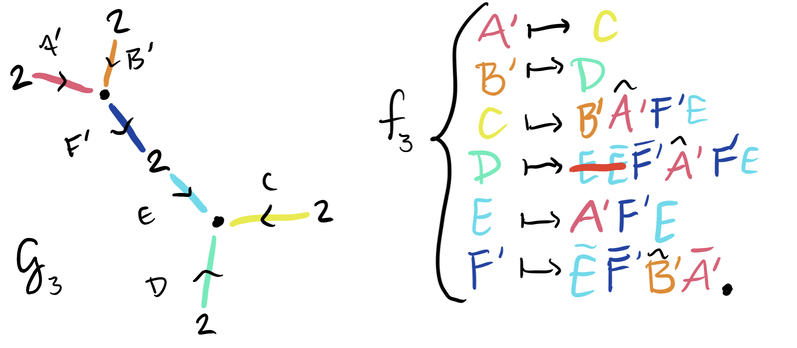

Let’s fold again, this time identifying all of $E$ with an initial segment of $\bar F$ . The correspondence $F \leadsto F'E$ yields a new map $f_3\colon \mathcal{G}_3 \to \mathcal{G}_3$ .

Now the Perron–Frobenius eigenvalue $\lambda_3$ is the largest root of $x^6 - 2x^5 - 2x^4 - 2x^3 + 5x - 2$ and satisfies $\lambda_3 \approx 2.875$ .

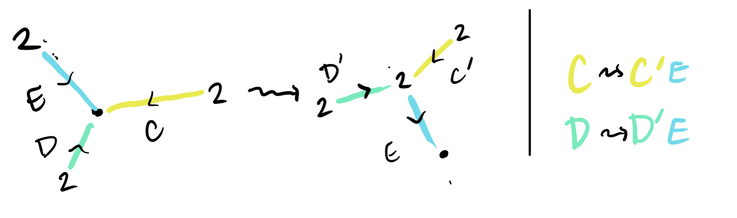

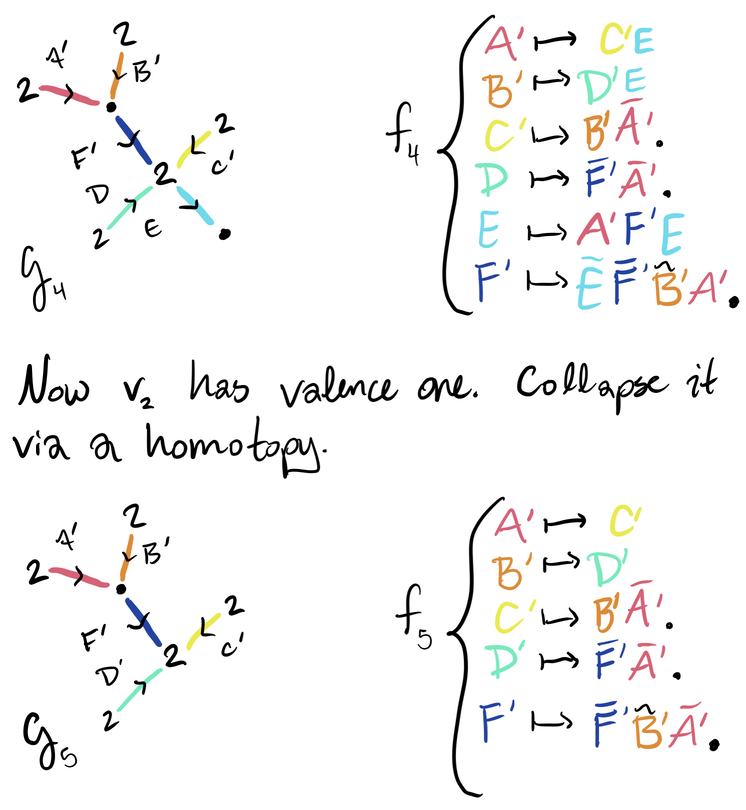

There are still illegal turns, so let’s fold $C$ and $D$ with $E$ to produce a valence-one vertex with trivial vertex group.

Folding doesn’t produce any cancellation, so the Perron–Frobenius eigenvalue is unchanged.

The valence-one homotopy does decrease the Perron–Frobenius eigenvalue; $\lambda_5$ is the largest root of $-x^5 + x^4 + x^3 + x^2 + x - 2$ and satisfies $\lambda_5 \approx 1.830$ .

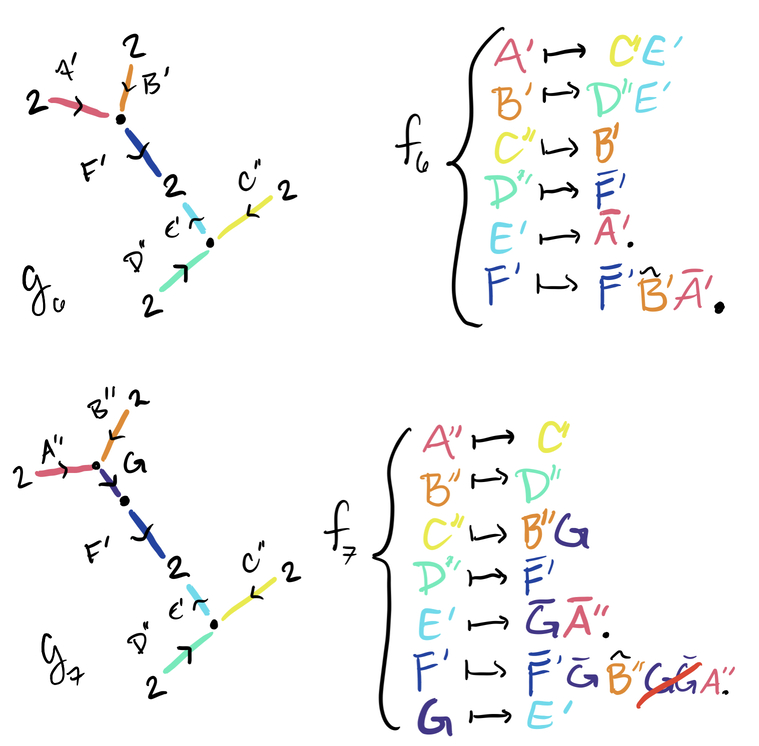

The image of $F'$ contains the illegal turn $\{\bar A',\bar B'\}$ , which is first mapped to $\{\bar C',\bar D'\}$ before degenerating. So we’ll fold $\bar D'$ and $\bar C'$ , then $\bar A'$ and $\bar B'$ , and then the interior of $F'$ if need be.

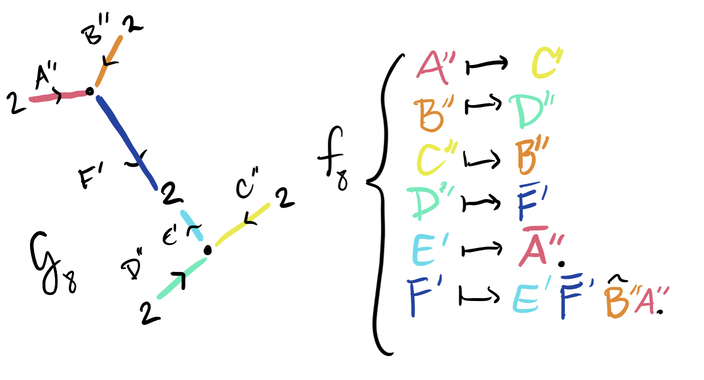

As it happens, the second fold produces nontrivial tightening; $\lambda_7$ is the largest root of $-x^7 + x^6 + x^5 + x^4 + x^3 - 2x^2 - 2$ and satisfies $\lambda_7 \approx 1.789$ . We have produced a vertex of valence two with trivial vertex group and would like to get rid of it via a homotopy. The eigenvector coefficient of the edge $G$ is larger than the eigenvector coefficient for $F'$ , so we collapse $G$ .

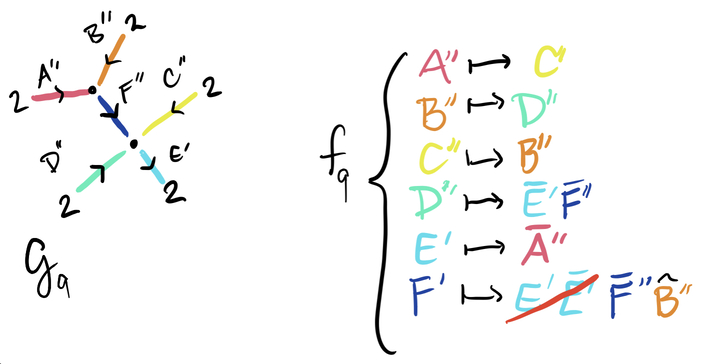

The Perron–Frobenius eigenvalue $\lambda_8$ is the largest root of $x^6 - x^5 - 2x^3 - x - 1$ and satisfies $\lambda_8 \approx 1.783$ . The turn $\{\bar E',\bar F'\}$ is illegal and in the image of $F'$ , so we fold them.

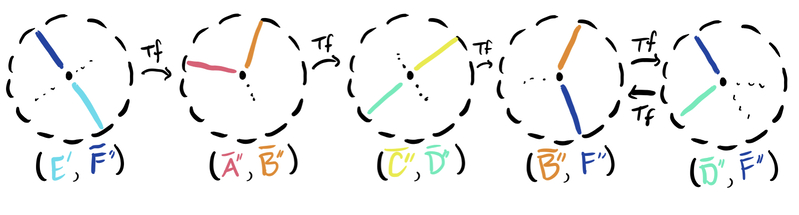

The Perron–Frobenius eigenvalue $\lambda_9$ is the largest root of $x^6 - x^5 - 2x^3 - x + 1$ and satisfies $\lambda_9 \approx 1.722$ . The only turns that we need to worry about in the image of edges of $f_9$ are $\{E',\bar F''\}$ and $\{\bar B'',F''\}$ .

As it turns out, both of these turns are legal, so this is a train track map! Indeed $\lambda_9$ is also the largest real root of $x^4 - x^3 - x^2 - x + 1$ , the polynomial we mentioned before in connection with $\sigma_1\sigma_2\sigma_3\sigma_4\sigma_1\sigma_2$ .