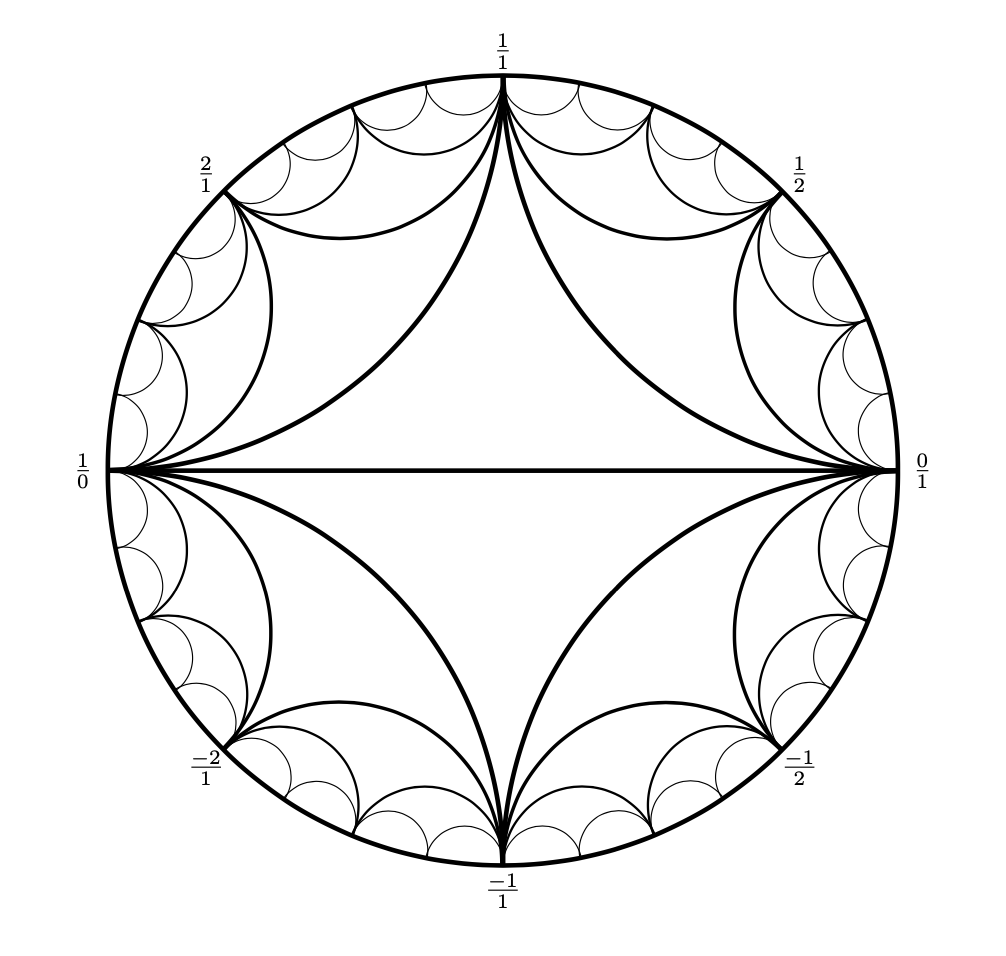

The Farey graph, or Farey diagram, is an object that appears in many guises throughout math. For me, it appears several times as a complex related to the outer automorphism group of a free group of rank two, but it has connections to things like continued fractions as well. The purpose of this post is introduce the Farey graph and prove a couple of basic properties of it.

The Farey graph has as vertices all rational numbers expressed as fractions $\frac{p}{q}$ in lowest terms with $q \ge 0$ , together with a vertex for $\frac{1}{0}$ . Two vertices $\frac{a}{b}$ and $\frac{c}{d}$ span an edge when the matrix $\begin{pmatrix} a & c \\ b & d \end{pmatrix}$ has determinant $\pm 1$ . Above is a picture; thanks to StackExchange user marchetto for the TikZ code for producing the Farey diagram, to which I mainly added numbers. I’d like to demonstrate that the visual properties of the Farey graph hold: namely, that every edge belongs to exactly two triangles, and that edges do not cross.

Edges belong to two triangles

In this section we will show that every edge of the Farey graph belongs to two triangles. The key tool will be a lemma I learned from Allen Hatcher’s Topology of Numbers.

Lemma. Suppose $a$ and $b$ are integers with no common divisor. If one integral solution of $ay - bx = n$ is $(x,y) = (c,d)$ , then the general integral solution is $(x,y) = (c + ka, d + kb)$ for integer $k$ .

Proof. Consider a general solution $(x,y)$ . Given our known solution $(c,d)$ , we see that $a(y-d) - b(x -c) = n - n = 0$ . Since $a$ and $b$ have no common factors, it follows that $a$ divides $x-c$ and $b$ divides $y-d$ . In fact, we have $a(y-d) = abk = b(x-c)$ , from which the result follows. $\blacksquare$

A variant on the proof shows that if $ac - bd = -n$ , then the general integral solution for $ax - by = n$ is $(ka - c,kb - d)$ .

Proposition. Suppose that $\frac ab$ and $\frac cd$ are in the Farey graph, and that $ad > bc$ . If $\frac xy$ is adjacent to both $\frac ab$ and $\frac bc$ , then $\frac xy = \frac{a\pm c}{b\pm d}$ .

Proof. Suppose $\frac ab$ and $\frac cd$ are as in the statement. Now suppose $\frac xy$ is adjacent to both $\frac ab$ and $\frac cd$ . Suppose first for definiteness that $ay - bx = 1$ . By the lemma, we have that $(x,y) = (ka + c, kb + d)$ for some integer $k$ . By assumption, we have $cy - dx = \pm 1$ , so the lemma shows that $(x,y) = (\ell c \mp a,\ell d \mp b)$ for some integer $\ell.$ Therefore we have $a(k \pm 1) = (\ell - 1)c$ and $b(k \pm 1) = (\ell-1)d$ , from which it follows that $(k \pm 1)(\ell - 1)(ad - bc) = 0$ . Therefore either $k = \mp 1$ or $\ell = 1$ , both of which imply $(x,y) = (c \mp a,d \mp b)$ . If instead we have $ay-bx = -1$ , then the conclusion is the same. We of course have $\frac{c \mp a}{d \mp b} = \frac{a \pm c}{b \pm d}$ . $\blacksquare$

The action of $\operatorname{SL}_2(\mathbb{Z})$

In this section we analyze the action of $\operatorname{SL}_2(\mathbb{Z})$ on the Farey diagram, proving that it is transitive on edges and triangles.

First let us define the action of $\operatorname{SL}_2(\mathbb{Z})$ on the Farey diagram. The action of $\operatorname{SL}_2(\mathbb{Z})$ on $\mathbb{Z}^2$ restricts to an action on the vertex set of the Farey diagram. Indeed, $a$ and $b$ are relatively prime if and only if there exists integers $x$ and $y$ such that $ax + by = 1$ if and only if $(a,b)$ is the first column of a matrix in $\operatorname{SL}_2(\mathbb{Z})$ if and only if there is an element of $\operatorname{SL}_2(\mathbb{Z})$ taking $(1,0)$ to $(a,b)$ . In terms of fractions, if $z = \frac{p}{q}$ is a vertex of the Farey diagram, then the action of $\begin{pmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{pmatrix}$ sends $z$ to

$\frac{az + b}{cz + d} = \frac{ap + bq}{cp + dq}.$This action preserves adjacency: the reader is encouraged to figure out why. Indeed, the action is transitive on edges: can you show that if $\frac ab$ and $\frac cd$ are adjacent in the diagram, there is an element of $\operatorname{SL}_2(\mathbb{Z})$ sending the edge between $\frac 01$ and $\frac 10$ to the edge between $\frac ab$ and $\frac cd$ ?

Finally, put a cyclic order on the vertex set of the Farey diagram by taking the cyclic order induced by the linear order on $\mathbb{Q} \cup \{\infty\}$ . That is, given three distinct elements $p$ , $q$ and $r$ in $\mathbb{Q}\cup\infty$ , say $(p,q,r)$ is cyclically ordered if $a < b < c$ or $b < c < a$ or $c < a < b$ holds. For example $(\infty,-2,0)$ is cyclically ordered.

Proposition. Suppose $p$ , $q$ and $r$ are the vertices of a triangle in the Farey diagram and that $(p,q,r)$ is cyclically ordered. Then there is an element of $\operatorname{SL}_2(\mathbb{Z})$ sending $(0,1,\infty)$ to $(p,q,r)$ .

Proof. Suppose $p = \frac cd$ and $r = \frac ab$ . Because $p$ and $r$ are adjacent in the Farey diagram, the matrix $\begin{pmatrix} a & c \\ b & d \end{pmatrix}$ has determinant $\pm 1$ .

Assume first that $ad-bc = 1$ , i.e. that $p < r$ . Then the claim is that $q = \frac{a+c}{b+d}$ , which is the image of $\frac 11$ under the matrix $\begin{pmatrix} a & c \\ b & d\end{pmatrix}$ . In other words, the claim is that $(p,\frac{a-c}{b-d},r)$ is not circularly ordered, for which we need to show that $p<\frac{a-c}{b-d}<r$ is false. Assume first that $b-d$ is nonnegative. Then $ad > bc$ implies $ab - ad < ab - bc$ , which implies $\frac ab < \frac{a-c}{b-d}$ , and the claim follows. Next assume that $b-d$ is negative. Then $ad > bc$ implies that $ad - dc > bc - dc$ , which implies $\frac{a-c}{b-d} < \frac cd$ , and the claim follows (Note that we assume that $d$ is nonnegative.)

Next assume that $ad - bc = -1$ , i.e. that $r < p$ . Then the claim is that $q = \frac{a-c}{b-d}$ , which is the image of $\frac 11$ under the matrix $\begin{pmatrix} a & - c \\ b & -d\end{pmatrix}$ in $\operatorname{SL}_2(\mathbb{Z})$ . In other words, the claim is that $(p,\frac{a+c}{b+d},r)$ is not circularly ordered, for which we need to show that it neither $\frac{a+c}{b+d} < r < p$ nor $r < p < \frac{a+c}{b+d}$ holds. In fact, $ad < bc$ implies $ab + bc > ab + ad$ holds, which implies $\frac{a+c}{b+d} > \frac ab$ . But, $ad < bc$ implies that $ad + dc < bc + dc$ , which implies that $\frac{a+c}{b+d} < \frac cd$ , and the claim follows. $\blacksquare$

In fact, the proof above shows that the matrix in $\operatorname{SL}_2(\mathbb{Z})$ is unique up to multiplication of all the entries by $-1$ . This corresponds to the matrix $\begin{pmatrix} -1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{pmatrix}$ , which generates the center of $\operatorname{SL}_2(\mathbb{Z})$ .

Corollary. The stabilizer of a triangle is isomorphic to $C_3 \times C_2 \cong C_6$ .

An explicit generator for the cyclic group of order $6$ stabilizing the triangle spanned by $(0,1,\infty)$ is $\begin{pmatrix} 1 & -1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}$ .

The proposition also yields an element of $\operatorname{SL}_2(\mathbb{Z})$ interchanging $0$ and $\infty$ : this element is $\begin{pmatrix} 0 & -1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}$ . This element is unique up to multiplication by $-1$ and has order $4$ , so we have proven the following.

Corollary. The stabilizer of an edge is isomorphic to $C_4$ .

Edges do not cross

We finish this post by proving that edges of the Farey diagram do not cross, in the sense that if $p$ and $q$ are adjacent and $r$ and $s$ are adjacent and $p$ , $q$ , $r$ and $s$ are all distinct, then if $(p,r,q)$ is cyclically ordered, then $(p,s,q)$ is also cyclically ordered. By results in the previous section, we may assume $p = 0$ and $q = \infty$ . That is, if $r = \frac ab$ is positive and $\frac cd$ is adjacent to $\frac ab$ , then $\frac cd$ is also positive. By swapping the roles of $r$ and $s$ if necessary, we may assume that $ad - bc = 1$ . Since we assume that $a$ , $b$ , and $d$ are positive integers, then we must have $c \ge 0$ in order to satisfy $ad -bc = 1$ .