This is the fifth post in a series on Katie Mann and Kasra Rafi’s paper Large-scale geometry of big mapping class groups. At the beginning, I mentioned that Mann and Rafi provide a classification of which $\Sigma$ have $\operatorname{Map}(\Sigma)$ generated by a coarsely bounded set under a hypothesis. The purpose of this post is to explore that hypothesis, which is called tameness. Additionally, I want to report on recent progress by Mann and Rafi in their note Two results on end spaces of infinite-type surfaces.

Characterizing self-similarity

Suppose $\operatorname{Ends}(\Sigma)$ is self-similar. Then the set of maximal ends $\mathcal{M}(\Sigma)$ is either a singleton or a Cantor set of ends of the same type; for if it were not, we could find a decomposition of $\operatorname{Ends}(\Sigma)$ into clopen subsets that have no hope of containing a clopen subset homeomorphic to $\operatorname{Ends}(\Sigma)$ . If we make the assumption that $\Sigma$ has no nondisplaceable finite-type subsurfaces, then the converse is also true.

A key observation in the proof is the following “swindle:” if $U_1,U_2,\ldots$ is a countable collection of pairwise homeomorphic, disjoint clopen subsets of $\operatorname{Ends}(\Sigma)$ with the property that the $U_i$ Hausdorff converge to a single end $\xi$ disjoint from all the $U_i$ , then fixing a homeomorphism $f_i \colon U_i \to U_{i+1}$ , the disjoint union of the $f_i$ extends continuously to a homeomorphism

$f\colon \{\xi\}\sqcup U_1 \sqcup U_2 \sqcup \cdots \to \{\xi\} \sqcup U_2 \sqcup U_3 \sqcup \cdots.$By Hausdorff convergence, we mean that the Hausdorff distance between $U_i$ and $\xi$ as compact subsets of $\operatorname{Ends}(\Sigma)$ goes to zero with $i$ , where the Hausdorff distance between $U_i$ and $\xi$ is

$\inf\{d(\zeta,\xi) : \zeta \in U_i\}.$(In general, if $\xi$ were replaced by an arbitrary compact subset $K$ , we would have to “symmetrize” the above by performing an analogous construction with the roles of $K$ and $U_i$ reversed and then taking a maximum.)

Stable neighborhoods and tame surfaces

Anyway, call a neighborhood $U$ of an end $\xi$ in $\operatorname{Map}(\Sigma)$ stable if for any smaller neighborhood $V \subset U$ , there exists a homeomorphic copy of $U$ within $V$ . When $\mathcal{M}(\Sigma)$ is a singleton or a Cantor set of ends of the same type, the proof that $\operatorname{Ends}(\Sigma)$ is self-similar shows that in fact each end in $\mathcal{M}(\Sigma)$ has a stable neighborhood. As it happens, all stable neighborhoods of an end are homeomorphic, and if $\xi \sim \zeta$ and one has a stable neighborhood, so does the other.

We say that $\Sigma$ is tame if every $\xi \in \operatorname{Ends}(\Sigma)$ that is either maximal or immediately precedes a maximal point has a stable neighborhood.

The partial order may be simplified

The first result of Mann–Rafi’s note that I want to report on is the following: recall the partial order on ends. One way of phrasing it is saying that $\xi \preceq \zeta$ if there is a homeomorphism of $\Sigma$ sending $\xi$ arbitrarily close to $\zeta$ . One way for this to be the case is if there is a homeomorphism actually taking $\xi$ to $\zeta$ . Actually this is the only way.

Theorem 1.2 (Mann–Rafi, building on Tsankov). If $\xi \preceq \zeta$ and $\zeta \preceq \xi$ , then there is a homeomorphism of $\Sigma$ sending $\xi$ to $\zeta$ .

The idea of the proof, which they attribute to Todor Tsankov, is that if $\xi$ and $\zeta$ have the same orbit closure under the action of $\operatorname{Map}(\Sigma)$ on $\operatorname{Ends}(\Sigma)$ (indeed, this is what it means to have $\xi \preceq \zeta$ and $\zeta \preceq \xi$ ), and their orbits are infinite and hence dense in their closure, then actually their orbits are comeager (their complement is a countable union of nowhere dense sets) and hence identical.

More on end spaces

A natural question to ask in view of the characterization of self-similarity above, is to what extent the no nondisplaceable finite-type subsurfaces condition is necessary. For example, supposing $\Sigma$ has a unique maximal end, is it true that $\operatorname{Ends}(\Sigma)$ is self-similar? The answer, given in Mann–Rafi’s note, is no. To construct such a surface, we need to be able to construct a countable collection of ends that are pairwise noncomparable.

Countable end spaces

First, we have to note that this is impossible in the case that $\Sigma$ is planar (genus zero) and has countable end space: the reason is that in this case, a classical result of Mazurkiewicz and Sierpinski says that $\operatorname{Ends}(\Sigma)$ is homeomorphic to the countable ordinal $\omega^\alpha\cdot m + 1$ , in the order topology, where $\alpha$ is a countable ordinal (allowing $0$ ), $m \ge 1$ is an integer, and $\omega$ denotes the first countable limit ordinal.

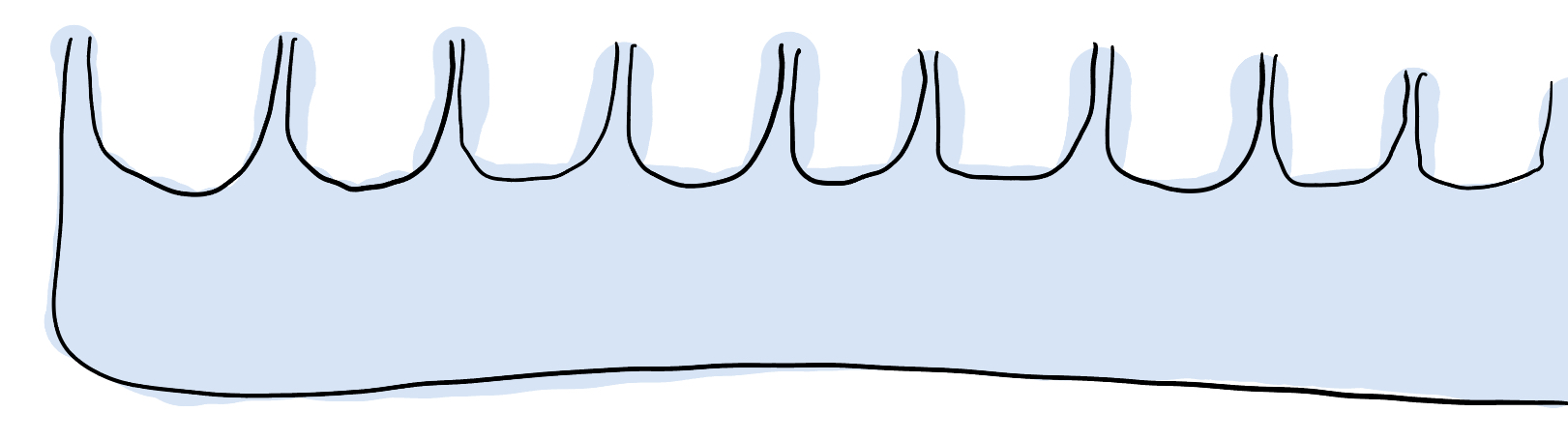

I find it difficult to think of ordinals directly in this way; I’m always having to translate this description into the language of surfaces. If $\alpha = 0$ , then $\omega^\alpha \cdot m + 1 = m + 1$ is a set of $m$ points with the discrete topology; so suppose $\alpha \ge 1$ . As a first case, suppose $m = \alpha = 1$ . This is the “flute” surface, with one maximal end (off to the right) accumulated by isolated planar ends.

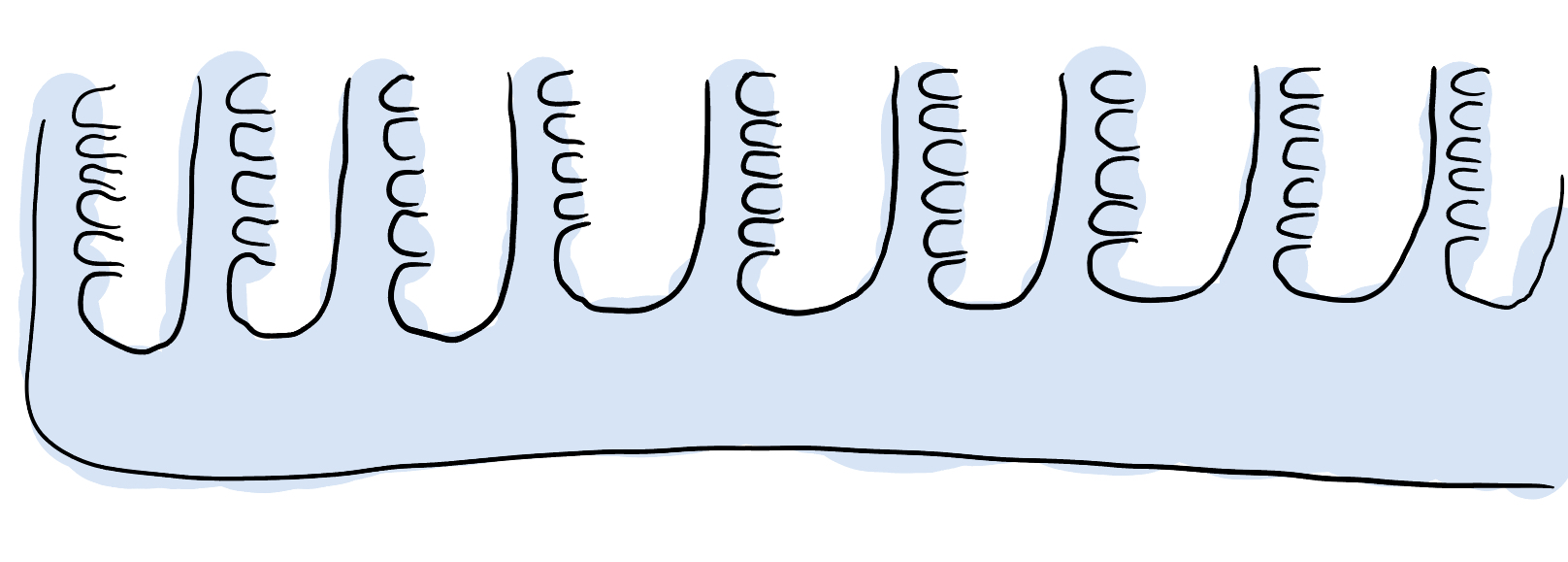

To increase $\alpha$ , take a countable collection of copies of the previous surface, and “flute” them together! So the “flute of flutes” surface with end space $\omega^2 + 1$ has a countable sequence of ends accumulated by isolated planar ends, all accumulating to one maximal end.

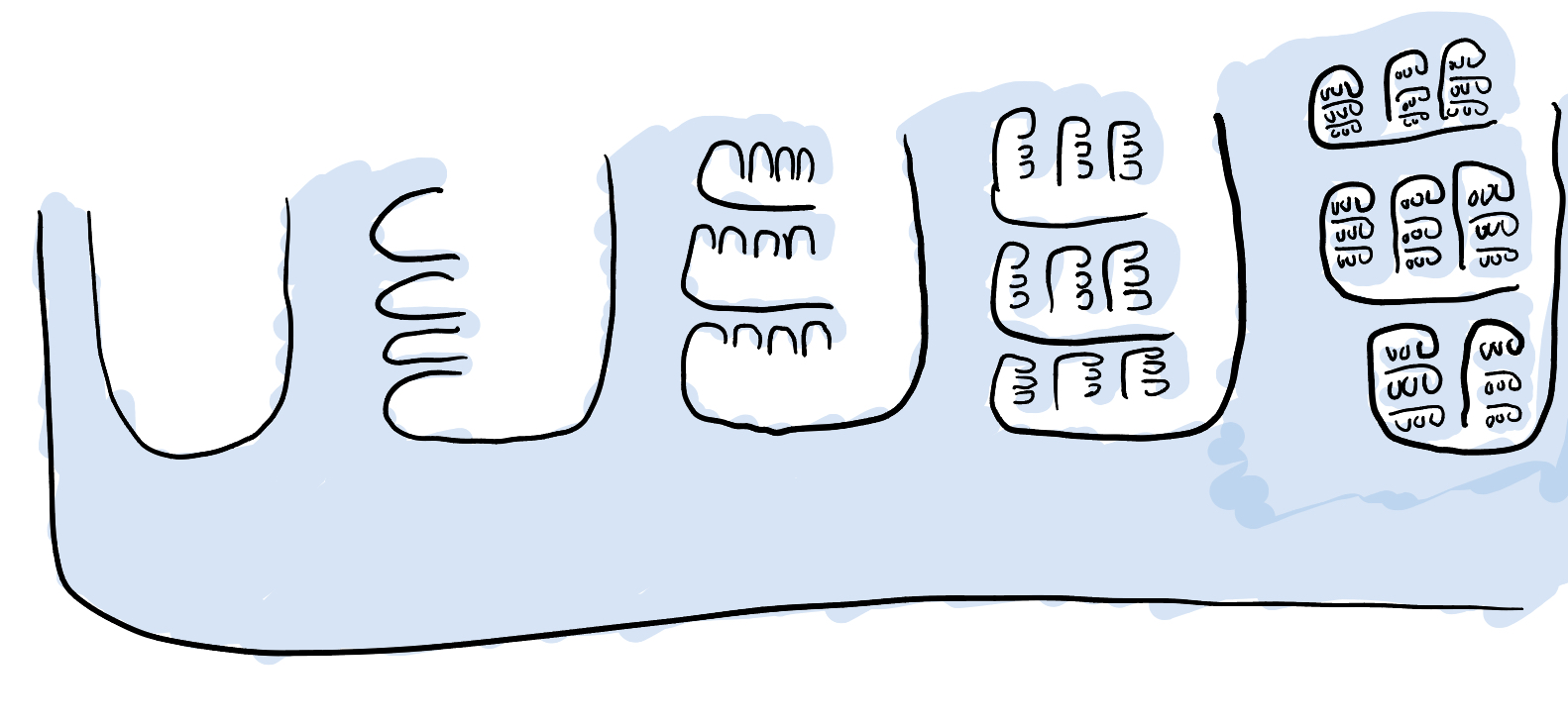

Okay, that works fine for successor ordinals, how about $\alpha$ a limit ordinal? Well, take a sequence $\beta_i$ of ordinals approaching $\alpha$ and for each $\beta_i$ take the “$\beta_i$ flute” and then flute together all these flutes. I attempted to draw it in the case of $\alpha = \omega$ , and now would like to call this surface “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” surface.

So now, to go from here to the general case where $m \ne 1$ , just take a connect-sum of $m$ copies of the “$\alpha$ flute”.

Anyway what was the point? The point was, the types of ends in each of these surfaces are linearly ordered based on whether they’re isolated, accumulation points of isolated points, accumulation points of accumulation points of isolated points, and so on. It’s not possible to even construct a single pair of noncomparable ends in this way!

By the way, the ordinal $\alpha$ is the Cantor–Bendixson rank of the maximal ends, i.e. the “(transfinite) number of times” you would have to remove isolated points to make the maximal ends isolated.

Noncomparable ends

Anyway, if we abandon one of “planar” or “countable”, suddenly it becomes possible to construct a countable collection of pairwise noncomparable ends.

We will think of each of these ends as being the unique maximal end of a surface.

Here’s the countable, non-planar construction: since the end space is countable and has a unique maximal end, we’re looking at an “$\alpha$ flute” for some ordinal $\alpha \ge 0$ . Consider $\beta \le \alpha$ . Pick out a subset of ends of the “$\alpha$ flute” homeomorphic to $\omega^\beta + 1$ and containing the maximal end. That is, think of the “$\alpha$ flute” as being built out of the “$\beta$ flute” by attaching flutes of lower complexity, but instead of isolated planar ends in the “$\beta$ flute”, take copies of the Loch Ness Monster—the surface with one non-planar end. So for example, if $\alpha = 2$ and $\beta = 1$ , the surface has isolated planar ends converging to non-planar ends which converge to the maximal end (which is therefore non-planar). As we vary the pair $(\alpha,\beta)$ , it’s not hard to argue that the maximal ends of the resulting “spotted flutes” are noncomparable.

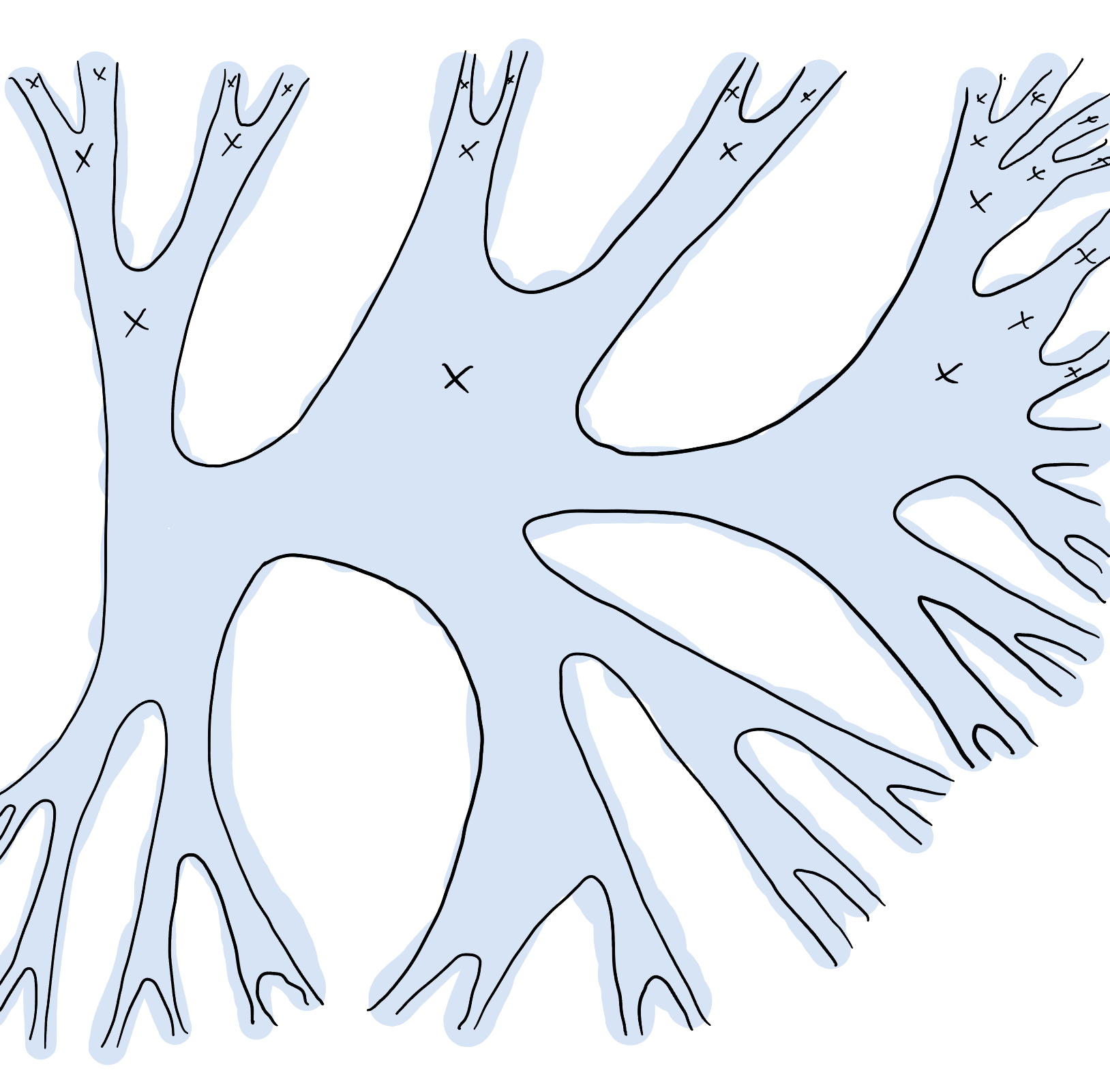

Here’s the uncountable, planar construction: take a Cantor tree—the planar surface with a Cantor set of ends and pick out one special end; think of it as being somehow in the “middle” of the tree, with a “top” half and a “bottom” half each with a Cantor set of ends intersecting precisely in this one end, which I’ll draw as going off to the right. If we think of the Cantor tree as being built out of pairs of pants, attach to the, well, crotch of each pair of pants in the “top” half, the “$n$ flute”. If $n = 0$ , this is just a puncture, which I’ve drawn as an “x” in the figure.

The special end is the unique maximal end of this surface, being accumulated by a Cantor set of ends which are accumulated by ends of Cantor–Bendixson rank $n$ as well as a Cantor set of ends which are not. As $n$ varies, we see that the maximal ends are pairwise noncomparable.

A unique maximal end that is not self-similar

Given our construction of at least countably many pairwise noncomparable ends $\{\xi_n\}$ , we can construct a surface with one maximal end that is not self-similar. We do this by fluting together a bunch of trees. Each end of each tree will have the sequence $\xi_0,\xi_1,\ldots$ as you go out, so each end of each tree will be of the same type—but! The trees will be different in the following crucial way. In the first tree, have one end of type $\xi_0$ , two of type $\xi_1$ , four of type $\xi_2$ , and so on, doubling each time. In the second tree, perform the same construction but with a delay, so one end each of types $\xi_0$ and $\xi_1$ , then two of type $\xi_2$ and so on. And in general the $N$ th tree will have one end of types $\xi_0,\ldots,\xi_{N-1}$ and then begin to double.

From here it’s a cute argument in finite sums to see that you can’t fit the first tree into the union of the first $M$ trees for any $M$ —can you see that goes? But since the first tree is separated from the maximal end, it must be sent away from the maximal end for this wild flute to have self-similar end space, so this is a contradiction!