This is the fourth post in a series on Katie Mann and Kasra Rafi’s paper Large-scale geometry of big mapping class groups. Truth be told, I’ve made many abortive attempts at writing this post. I want to describe the classification of locally coarsely bounded mapping class groups in a way that is useful and not too technical. I’m going to try and talk through two examples that Mann–Rafi give at the beginning of the paper, and then state the classification theorem at the end of the section.

A locally coarsely bounded example

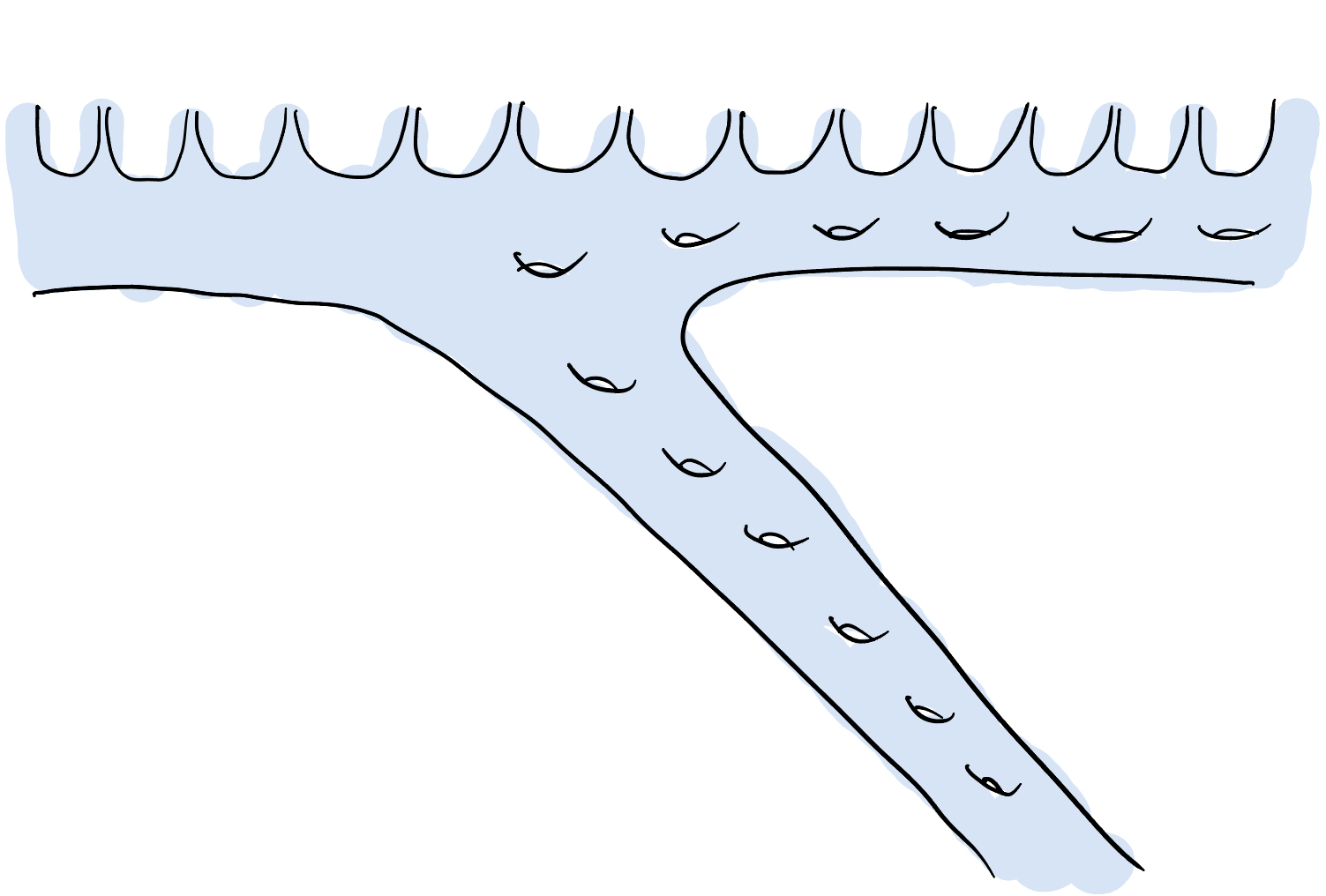

Consider the following surface $\Sigma$ first introduced in the first post in the series.

As a reminder, $\Sigma$ has three maximal ends, two of which are accumulated by punctures (isolated, planar ends), and two of which are accumulated by genus; the two sets of two overlap in exactly one end.

Consider a pair of pants $P$ in $\Sigma$ which separates each of the maximal ends from the others. I claim that $U_P$ , the set of mapping classes which have representative homeomorphisms preserving $P$ and restricting to the identity on $P$ , is a coarsely bounded neighborhood of the identity in $\operatorname{Map}(\Sigma)$ .

How would one go about showing this? To say that $U_P$ is coarsely bounded says that for any neighborhood $U$ of the identity, there exists a finite set $F$ in $\operatorname{Map}(\Sigma)$ and $k \ge 1$ such that $U_P \subset (FU)^k$ . Now, $U$ contains a neighborhood of the form $U_S$ , where $S \supset P$ is a finite-type subsurface. We will show that there is a finite set $F$ and $k \ge 1$ so that if $[g] \in \operatorname{Map}(\Sigma)$ satisfies $g|_P = 1$ , then $g \in (FU_S)^k$ , hence in $(FU)^k$ .

Now, since $g|_P = 1$ and $\Sigma - P$ has three components, we may write $g$ as $g_1g_2g_3$ , where each $g_i$ is supported on a component of $\Sigma - P$ . We will focus on each $g_i$ separately.

Given one of the maximal ends $\xi$ , consider a subsurface $\Sigma_\xi$ of $\Sigma$ in the complement of $S$ with one boundary component and having $\xi$ as an end. For example, maybe $\xi$ is the end accumulated only by punctures and $\Sigma_\xi$ is determined by a curve in the complement of $S$ which cuts off $\xi$ from the other two ends. We will construct a homeomorphism $f_\xi \colon \Sigma \to \Sigma$ with the property that $f_\xi(\Sigma_\xi)$ contains (up to isotopy) the complementary component of $\Sigma - P$ with end $\xi$ .

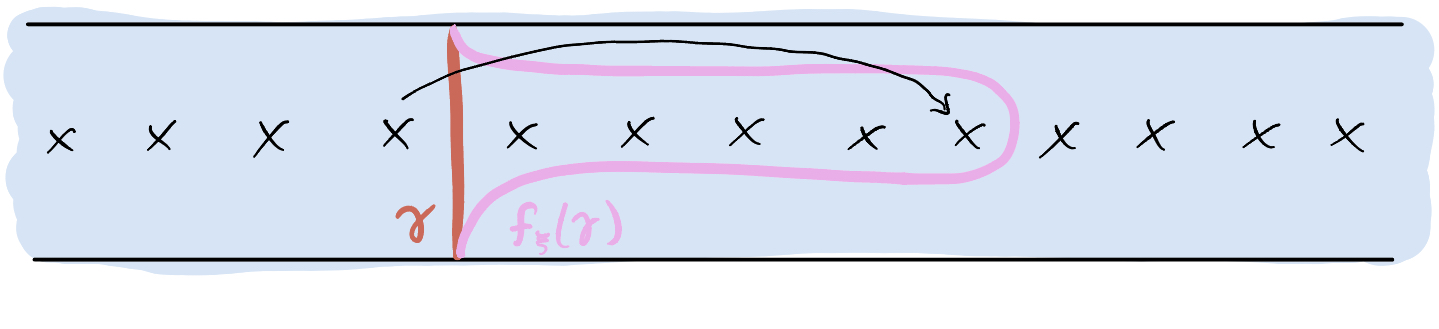

Here is the construction: since two (this is important) ends of $\Sigma$ are accumulated by punctures, we can embed a “strip of punctures” into $\Sigma$ in a proper way. By a strip of punctures I mean begin with an infinite strip $\mathbb{R} \times [0,1]$ , and then remove each point of the form $(n, \frac 12)$ for $n \in \mathbb{Z}$ . The homeomorphism $f_\xi$ will be supported on this strip of punctures, and what it does is “shift” the punctures by some integer, sending the (missing) points $(n,\frac 12)$ to $(n + m, \frac 12)$ for some fixed integer $m$ , and then tapering to the identity on the boundary $\mathbb{R} \times \{0\}$ and $\mathbb{R} \times\{1\}$ . Here is a picture with an arc $\gamma$ connecting the two boundary components illustrated along with its image $f_\xi(\gamma)$ .

Anyway, you should convince yourself that by choosing the shift map $f_\xi$ appropriately, we may satisfy the condition that $f_\xi(\Sigma_\xi)$ contains the complementary component of $\Sigma - P$ with maximal end $\xi$ , at least up to isotopy. So if $g_i$ is supported on that complementary component $C$ , $f_\xi^{-1} g f_\xi$ is supported on $f_\xi^{-1}(C)$ , which is, up to isotopy, contained in $\Sigma - S$ !

The story is similar for the end accumulated by genus; instead of shifting a strip of punctures, we shift a “strip of handles”. For the end accumulated by both genus and punctures, we shift both a strip of handles and a strip of punctures off to different ends. The finite set $F$ is the set of all these shift maps and their inverses, and $k$ is, doing a little arithmetic, $2 \cdot 3 = 6$ , since each $g_i$ is in $FU_SF$ .

A non-example

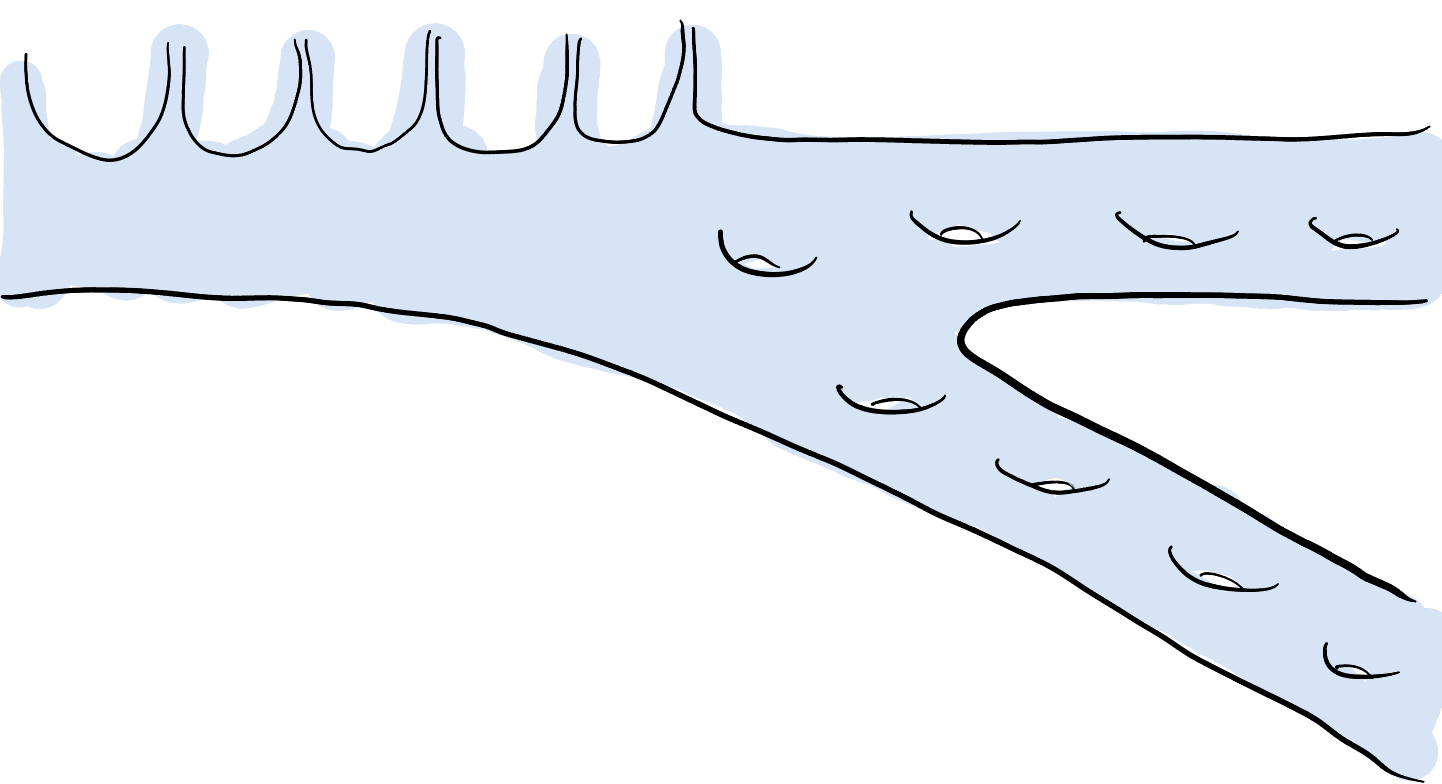

Now consider a surface $\Sigma'$ that is similar to $\Sigma$ except that only one maximal end is accumulated by punctures, and the other two are accumulated by genus only.

With $\Sigma$ , we made use of the fact that $P$ separated each of the finitely many maximal (types) of ends into self-similar neighborhoods. We can mimic this construction to define finite-type subsurfaces $P'$ of $\Sigma'$ ; for example a pair of pants which separates all the punctures from all the genus and also separates the two ends accumulated by genus. But a key feature of $\Sigma$ is missing from $\Sigma'$ : we cannot shift a strip of punctures away from one end and toward a different end. This changes the situation so much that I claim the following: no matter what finite-type subsurface $P'$ of $\Sigma'$ you choose, $\Sigma' - P'$ contains a finite-type subsurface which is nondisplaceable in $\Sigma'$ . This implies, by our observation in a previous post, that $U_{P'}$ is not coarsely bounded, so since $P'$ was arbitrary and the sets of the form $U_{P'}$ as $P'$ varies forms a neighborhood basis of the identity in $\operatorname{Map}(\Sigma')$ , we see that $\operatorname{Map}(\Sigma')$ is not locally coarsely bounded.

To see that $\Sigma' - P'$ contains a nondisplaceable finite-type subsurface, take an annulus $A$ in the complement of $P'$ whose core curve separates the end $\xi$ accumulated by punctures from $P'$ and the two ends accumulated by genus. Note that there are finitely many punctures in one component of the complement of $A$ , and although the punctures themselves do not have to be preserved by a homeomorphism $f\colon \Sigma' \to \Sigma'$ , the number of punctures in the component of $\Sigma' - f(A)$ not containing $\xi$ in its end set remains the same, call it $N$ . The core curve of $A$ is, up to isotopy, the only curve separating these particular $N$ punctures and all the genus of $\Sigma'$ from $\xi$ . But if we swap any of the $N$ punctures for different punctures via some homeomorphism $f$ , then $f(A)$ and $A$ must intersect! Thus, while strictly speaking $A$ may not be nondisplaceable (push it off of itself entirely by a homeomorphism isotopic to the identity), any sufficiently complex finite-type subsurface containing $A$ will be nondisplaceable.

The statement of the classification theorem

These two examples demonstrate the key ideas of the classification theorem: if $\Sigma$ is to be locally coarsely bounded, there must be, it’s not too hard to argue, finitely many types of maximal ends.

If $U_S$ is to be a coarsely bounded neighborhood of the identity in $\operatorname{Map}(\Sigma)$ , it turns out $S$ must separate the maximal ends of different types from each other, each complementary component must have infinite or zero genus (otherwise we would find nondisplaceable subsurfaces) and each maximal end must have not only a self-similar neighborhood determined by the decomposition, but it must be so strongly self-similar that we can construct these “shift” homeomorphisms like we did in the example of $\Sigma$ .

As it happens, $S$ is allowed to additionally cut off some infinite-type pieces which contain no maximal end—as long as we can move these “peripheral” pieces into some piece containing some maximal ends.

There is one exceptional case to the discussion above that isn’t well-spelled out in the Mann–Rafi paper: if $\Sigma$ has finitely many punctures, then punctures are maximal ends. It is convenient to insist that each component of $\Sigma - S$ have infinite type, but we cannot do this and also insist that the punctures have their own self-similar neighborhoods: such a neighborhood in $\Sigma$ would be just the puncture itself, which clearly does not have infinite type. Fortunately in this case the answer is clear: just include the punctures in $S$ .

Here is a possibly too verbose statement of the theorem.

Theorem 5.7 (Mann–Rafi). There exists a coarsely bounded neighborhood of the identity in $\operatorname{Map}(\Sigma)$ if and only if there exists a finite-type subsurface $S$ of $\Sigma$ with the following properties.

(1) Each boundary component of $S$ is separating, each complementary component of $\Sigma - S$ is of infinite type and has infinite or zero genus.

(2) Each of the finitely many complementary components of $\Sigma - S$ are either “big” or “small” according to whether their end sets contain a maximal end or not. If $C$ is a “big” component, each maximal end of $C$ is in fact maximal in $\Sigma$ .

(3) The end sets of “big” components are self-similar (and so contain either a single maximal end or a Cantor set of maximal ends of the same type) and for each maximal end $\xi$ in a “big” component $C$ , there exists, for any subsurface $\Sigma_\xi$ with one boundary component containing $\xi$ in its end set, a homeomorphism $f \colon \Sigma \to \Sigma$ with the property that $f(\Sigma_\xi) \supset C$ .

(4) For each “small” component $P$ , there exists a “big” component $C$ and a homeomorphism $f\colon \Sigma \to \Sigma$ exchanging $P$ with a subsurface of $C$ ; equivalently the end set of $P$ is homeomorphic to a clopen subset of the end set of $C$ .

Moreover, if such a subsurface $S$ exists, $U_S$ is a coarsely bounded neighborhood of the identity. We may always take $S$ to have genus zero if $S$ has infinite genus, and genus equal to the genus of $\Sigma$ otherwise. If $\Sigma$ has finitely many punctures, we may assume $S$ contains all of them.